A quarter-century ago, David Saylor shepherded the epic Harry Potter fantasy series onto U.S. bookshelves. As creative director of children’s publisher Scholastic, he helped design and execute the American editions of the first three novels in the late 1990s.

But when the manuscript for J.K. Rowling’s fourth book landed on his desk, Saylor sat up straight: It was huge. Bigger, more complex and narratively intricate than virtually any storybook ever aimed at children.

“I had to really think,” he said in a recent interview. “‘How are we going to typeset this book? How are we going to print a million copies? How are we going to get enough paper?’”

Bound and shipped, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire clocked in at a formidable 734 pages—2.5 pounds. It was, of course, another in a series of massive hits that collectively spent a decade atop The New York Times Bestseller List, ensnaring both children and adults, including most of Saylor’s friends.

He jokes that until the advent of Potter, “mostly no one cared that I worked in children’s books.” As excitement for the series grew, friends would ask him when the newest installment was due . . . and what happens next?

“Suddenly my job became important,” he said.

But the book and its six co-volumes now serve another purpose: They’re an eloquent proof point in an ongoing conversation in the publishing world: Are kids still reading books?

By the time Potter arrived, Saylor had lived through waves of predictions about the next extinction-level event to doom his industry. First it was TV, then video games. Before that it was radio and comic books, once derisively called “the ten-cent plague.”

“I’m only slightly jaded by these reports,” said Saylor, 65, “only because people are always predicting that kids are going to stop reading, and that the end of publishing is near.”

This time, it feels different.

Even as children’s publishing explodes with new talent and excitement from fans online, new distractions and diversions are precipitously driving down the share of young people who read for fun. It’s a long-simmering problem that even the optimist Saylor acknowledges his industry must confront.

‘The reading class’

Over the course of two generations, from 1984 to 2023, the proportion of 13-year-olds who said they “never or hardly ever” read for fun on their own time has nearly quadrupled, from just 8% to 31%.

During that time, the percentage of middle-schoolers who read for fun “almost every day” has fallen by double digits, according to surveys conducted for the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the test widely known as “the nation’s report card”: In 1984, 35% of middle school kids read for fun almost every day. By 2023, it was just 14%.

The phenomenon is part of a larger shift away from reading, research suggests: A new study from the University of Florida and University College London found that daily reading for pleasure has dropped more than 40% among adults over the last two decades, “a sustained, steady decline” of about 3% per year.

Findings like these have sparked fears that, after more than a century of steadily expanding literacy, reading is devolving into an act relegated to a small group of elites, a “reading class” that enjoys books while the rest of us see them as, in the words of scholar Wendy Griswold, “an increasingly arcane hobby.”

It’s a strange and thorny problem that in some sense seems contradictory: If you followed around a young person for a day, you’d likely see that she is reading constantly, but often in tiny fragments. In addition to school assignments, she’s taking in a ton of atomized content: alerts, text messages, memes and social media posts. All those bits add up for sure—one study found that the typical American reads the equivalent of a slim novel every day—but it isn’t the same as sitting down to read a book.

For young people, that’s having downstream effects, with NAEP reading scores slumping even before the pandemic and college professors increasingly reporting that students are uncomfortable tackling long reading assignments, let alone complete books.

Adam Kotsko, an assistant professor who teaches in the Great Books School, a discussion-based classics program at North Central College in Naperville, Ill., recently reported that his students are intimidated by any reading longer than 10 pages. They seemingly emerge from readings of as little as 20 pages, he said, with “no real understanding.”

That has put pressure on professors to design courses with fewer readings: “I got to a point where I was cutting to the bone so much that there wasn’t even enough to discuss in some class sessions,” he said in an interview. “It seems like the habits of sustained reading are not being taught in the first place, in some cases, and they’re just being replaced with nothing.”

While COVID lockdowns took a toll on reading, the problem predates the pandemic. Many observers point to several possible culprits, including schools’ fraught approaches to reading instruction and two decades of test-driven K-12 school pedagogies, which often de-emphasize fiction in favor of short non-fiction passages.

This has all taken place amid the dawn of smartphones—the iPhone turned 18 in June—and the rapid, unregulated rise of social media. So Kotsko and his colleagues are careful not to place the blame on students’ shoulders, but on a schooling and media ecosystem they can’t control.

“We are not complaining about our students,” he wrote recently. “We are complaining about what has been taken from them.”

‘Continuous partial attention’

Gabriel Baez, 15, said phones are “a big distraction” at his South Florida charter school. As soon as teachers give students even a moment of downtime, the phones come out. Several teachers have begun requiring students to stash them in special pouches during class. “No distractions—that’s the only thing that I think helped a lot of us.”

A sophomore, Baez said he’s excited to read the science fiction thriller Ready Player One—a novel about, of all things, video games. He loved the 2018 Steven Spielberg movie, but said most days he’s overscheduled and barely able to find a minute to open a book.

He’s in class from 7 a.m. to 2 p.m., then does homework until 5 p.m. Dinner is at 6 p.m., then he studies a bit more. From 7 to 8 p.m. it’s soccer training, then bed so he can wake up early and do it all again. “I really don’t have time unless I decide to substitute something.”

For many young people, school is what gets in the way of books.

Julia Goggin, 15, grew up reading books and loving them. She consumed the first few Harry Potter books unassisted in second grade and finished the series by fourth grade. She read a lot in middle school.

In high school? Not so much.

Like Baez, she’s heavily scheduled, running cross country in the fall and track and field in the winter. She’s in her school’s theater group, which means after-school rehearsals. Then homework. All of it leaves little time for reading anything aside from school assignments.

“If a school is too overbearing about forcing kids to read a lot, it makes them not want to read for fun because it’s not fun anymore,” she said. “Because school isn’t fun.”

A junior at a private high school in Wilmington, N.C., Goggin enjoys reading, but said her two younger brothers, eighth- and ninth-graders, don’t. “They never got into reading the same way I did when they were little. Since then, I guess, they’ve just played video games instead. That’s, like, all they do all day.”

Over the years, she has noticed a change in herself: As a kid, she read for relaxation. “But now all I want to do is scroll on TikTok, which is really bad,” she said with a laugh. “Now I have to be more conscious: Instead of going on my phone, I have to make the decision to read, which is different than before. When I was younger, it was just a default.”

To be sure, young people in the U.S. are reading words—lots of words. Perhaps more than ever.

In her most recent book, the literacy scholar Maryanne Wolf noted that research from as far back as 2009 found that the average American reads what amounts to 34 gigabytes of information, or about 100,500 words, daily—from newspapers, magazines, books, games, messages and social media posts. For a bit of perspective, To Kill a Mockingbird, the Harper Lee classic, clocks in at about 100,000 words.

While all that grazing certainly adds up, Wolf said, it’s “rarely continuous, sustained, or concentrated.” Rather, those 34 gigabytes represent “one spasmodic burst of activity after another.”

She said the fact that young people are reading all those words should comfort no one. “It means nothing.” The inability—or the unwillingness—to go deeper is what’s more important. “I think we have, really, a demise of deep reading, which for me is synonymous with critical thinking and empathy and the beauty of the reading act.”

While the 20th century saw literacy rates in the U.S. climb steadily, technological developments such as movies, radio, TV and the Internet shifted modern culture away from reading and writing and toward visual and oral communication. One unintended result: at least two generations of young people who see books and reading as optional.

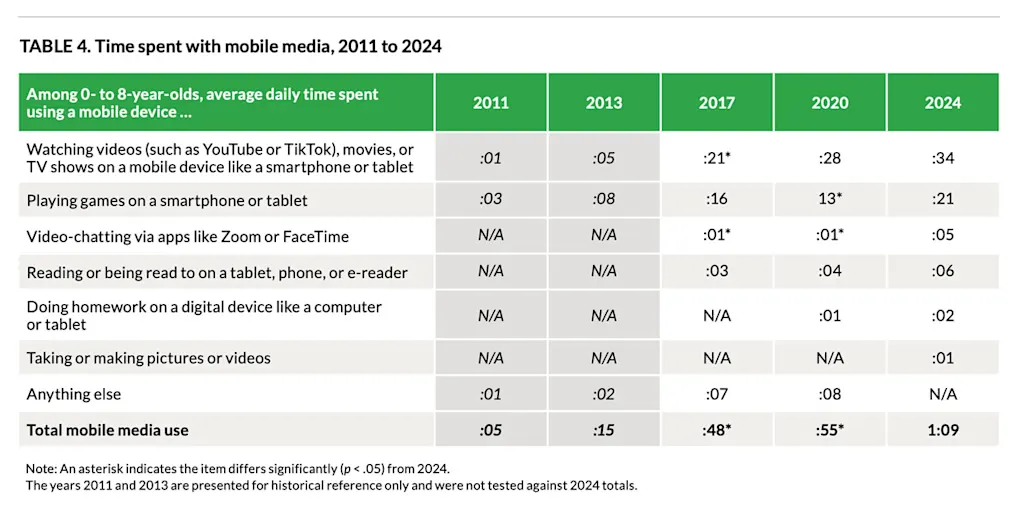

In the meantime, 65% of 8-to-12-year-olds now have an iPhone or other smartphone, according to a 2024 survey by the market research group YPulse—and 92% of 8-to-12-year-olds are on social media, where they’re inundated with memes and short-form videos.

Carl Hendrick, a Dublin-born professor at Academica University of Applied Sciences in Amsterdam and co-author of the 2024 book How Learning Happens, accuses this generation’s parents of all but abdicating their responsibilities.

He likens smartphones’ cognitive disruptions to the health effects of cigarettes, recalling that he grew up in Ireland at a time when smoking was ubiquitous. “You could smoke on buses—you could smoke on airplanes. You could smoke anywhere. We look back on that now with horror. And I think the same thing will be true of phones. We’ll go, ‘How did we allow 11-year-olds to go onto social media?’”

Hendrick, who has emerged internationally as a leading advocate for improving classroom instruction via better understanding of learning science, said digital distractions are taking a toll, hijacking kids’ ability to engage their working memory on difficult texts and problems. That kind of laser-like focus, he said, is rapidly disappearing from our lives due to the “weaponized distraction” of social media. “It’s at an extraordinary level of sophistication to try and grab your attention,” he said.

In a recent Substack newsletter, he laid down the gauntlet: “Solitude, slowness and sustained attention are no longer default states but acts of resistance. And as those conditions erode, so too does the possibility of the moral work that deep reading once quietly performed.”

While social media sites are the latest offenders, the phenomenon is hardly new. In 1998, the sociologist and computer researcher Linda Stone coined the term “continuous partial attention” to capture the ways in which the first digital television networks allowed users to “connect and be connected” 24/7. She described a kind of early FOMO, or “fear of missing out.” But it also generated an artificial sense of “constant crisis,” a dopamine-generated high alert that’s hard to extinguish.

By contrast, Hendrick said, giving oneself over to reading deeply, whether it’s literature, philosophy or any complex text, offers something more: a rehearsal for real life, and for the patience we need to deal with one another. “It is a rehearsal in understanding before judging, listening before reacting,” he wrote recently. “This is not merely a virtue. It is a survival skill for a pluralistic, tolerant society.”

Ironically, one of the big drivers of the discredited “whole language” movement was to foster a love of books and reading. But what educators missed at the time was that not teaching all kids to read proficiently at a young age meant reading became “more and more laborious” as they got older, since they couldn’t handle more complex texts, said Holly Lane, director of the University of Florida Literacy Institute.

“Nobody likes doing something that they’re not good at,” she said. “They may love the idea of reading, but they don’t like the act of reading.”

That, to many observers, is the original sin of the reading problem: the nation’s uneven commitment to teaching reading in ways we now know are mo

Melden Sie sich an, um einen Kommentar hinzuzufügen

Andere Beiträge in dieser Gruppe

Google dodged a bullet Tuesday when a federal judge ruled the company does no

Grab is a rideshare service-turned superapp, not available in the U.S. but rapidly growing in Southeast Asia. It’s even outmaneuvered global players like Uber to reach a valuation north of $20 bil

There’s no other phone I’d rather be using right now than Samsung’s Galaxy Z Fold7—and that’s a problem.

I’ve been a foldable phone appreciator for a while now, and a couple of years ago

One of the most powerful buttons on your phone is also one of the easiest to ignore.

I’m referring to the humble “Share” button, a mainstay of both iOS and Android that unloc