Perched on a dusty high desert plain about 100 miles north of downtown Los Angeles, the Mojave Air and Space Port looks more like a final destination for aerospace experiments than a stepping stone to the stars. A field with dozens of decommissioned commercial jetliners bakes in the early morning sun–it’ll eventually hit 110 degrees around noon–and the small shacks set between dusty roads and cracked pavement look mostly empty.

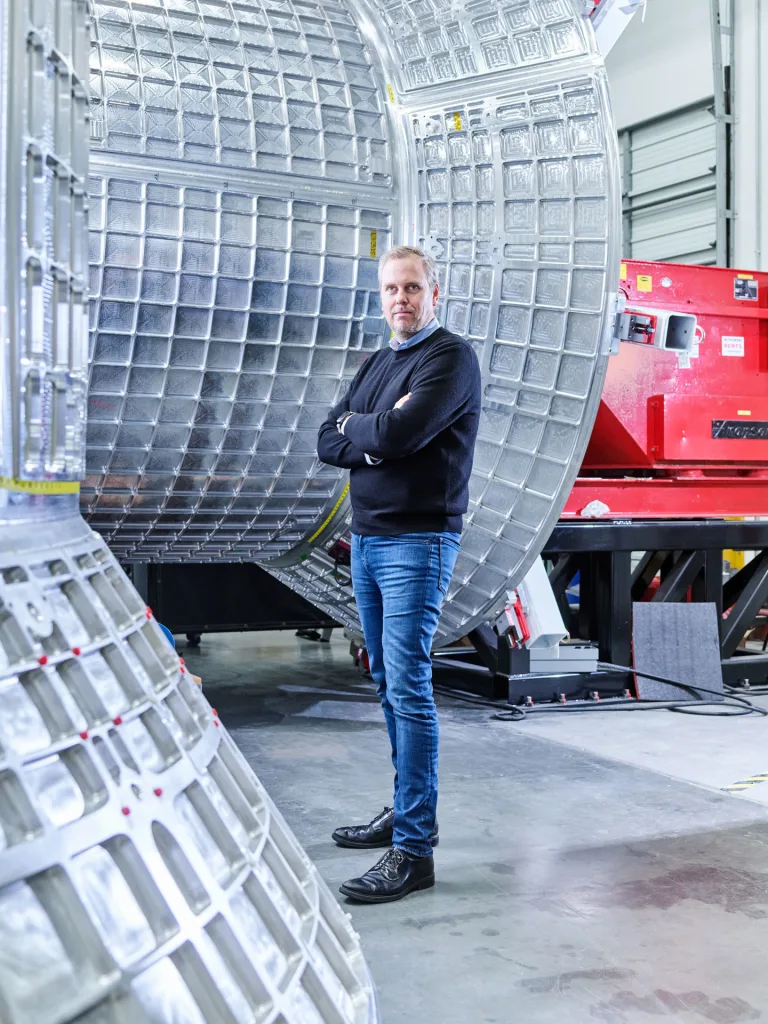

But drive past cracked airstrips and barbed wire gates, and—with the right security clearance—you may be able to walk up and touch the exterior of the next orbital space station: a 2-ton cylindrical aluminum module built by the startup Vast. Called Haven-1, it currently hangs from a 50-foot-tall steel scaffold while it undergoes extreme pressure testing, one of many complicated engineering milestones it needs to hit before its planned launch in May 2026.

Before engineers can install the module’s instrumentation, electronics, and life-support systems, they need to repeatedly pressurize the structure to 2.4 times Earth’s atmosphere to test its workmanship. Massive hoses hooked up to a trio of multistory liquid nitrogen tankers inflate the station—an isogrid metal shell that resembles a waffle cone—with nitrogen gas, like a kid’s birthday balloon. Observers need to stand at least 236 feet away in case bolts or brackets burst. During a visit in May, workers were welding and reinforcing the steel scaffold to make sure the structure can withstand a grueling and aggressive series of stress tests that will see the cabin inflated and deflated 200 times in a row.

Vast is racing against the clock to launch the world’s first commercial space station—independently, in-house, and in record time. It’s an audacious effort, made possible by the retirement of an icon: the International Space Station, a fixture of childhood imaginations and of humanity’s exploration of space since its first section was launched in 1998. It’s now set to be decommissioned in 2030, via a guided crash into the Pacific Ocean, and Vast wants to replace it.

“We’re going from an unknown to a formidable competitor,” says Vast CEO Max Haot, a Belgian-American serial entrepreneur. Founded in 2021 by American crypto entrepreneur Jed McCaleb, who served as CEO until Haot’s arrival in 2023, Vast has grown to a team of nearly 1,000 people intent on building the next generation of human habitation in space. The company is entirely funded by McCaleb, who has invested $1 billion in the startup.

NASA launched a competition for its Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations (CLD) program five years ago, setting a date of 2026 to choose a team and design to eventually replace the ISS. Vast wasn’t even around when the space agency awarded three teams seed funding to develop their visions: Starlab, Northrop Grumman, and a collaboration between Sierra Space and Blue Origin. That’s led Vast to adopt an accelerated approach that it hopes will ultimately prove its efficiency. To lap more established competitors, Haot is pushing his company to launch a prototype model before anybody else even submits their final proposal. Haot refers to other prospects as “paper designs.” Vast is already in the building phase.

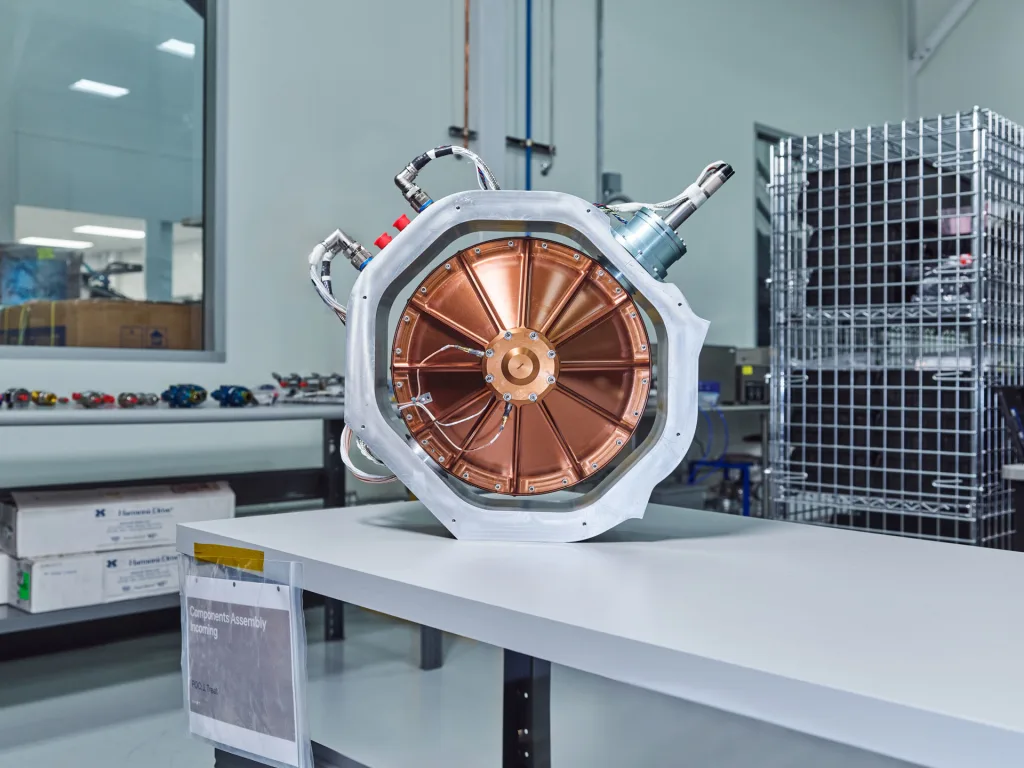

At the company’s sprawling 190,000-square-foot factory in Long Beach, a three-building complex once meant to be an Amazon warehouse, the deadline is palpable. There are space gadgets around every corner of the bustling workshop floor. In the back, staff are testing a device called a CMG (control moment gyroscope), fast-moving flywheels that will spin and orient the capsule. One set has been spinning for two and a half years to test its durability. A few stations away, massive chunks of raw aluminum are being cut via water jet and plasma welded into gridded exterior panels. Next door, quality control engineers are shooting those panels with a special gun that simulates orbital velocity, to ensure they can withstand the impact of small meteorites or space debris. Visitors can even tour a full-scale model of the white, wood-paneled station interior, dubbed the Haven Experience; weightlessness, sadly, not included.

Vast is at the forefront of a generational technological shift that’s underpinning the next push into space. Vast and its competitors aren’t radically reinventing the tech that made the original ISS possible. Instead, they’re attempting to launch a space station in a better, faster, and cheaper manner. The ISS, with an estimated $150 billion construction budget, was a custom made Italian sports car. The space stations that Vast and its ilk are trying to build are more an assembly-line luxury sedan, still pricy, but ultimately much more accessible.

Mason Peck, a Cornell professor and a former NASA chief technologist, says that while tech billionaires like McCaleb are bankrolling or running many key startups, building out more private, commercial ways to get to space “tends to democratize access.”

From crypto to the moon

McCaleb made his estimated $2.9 billion fortune by founding key cryptocurrency projects and following his hunches. He launched the Tokyo-based Mt. Gox Bitcoin exchange in 2010 after becoming interested in Bitcoin. To create the exchange, he repurposed an old website that he had made for trading Magic: The Gathering cards. (The domain name originally stood for Magic the Gathering Online Exchange.) In 2011, he sold the site, which at one point was handling 70% of global bitcoin transactions. It collapsed a few years later after losing nearly $350 million in Bitcoin due to hacks. By then, McCaleb had moved on, founding the cryptocurrency Ripple, which has provided the bulk of his fortune, and then Stellar, an online payment system.

McCaleb explains his decision to step away from Stellar and divert more than a third of his crypto fortune to a space startup as an opportunity to follow his passion. Humankind, he believes, needs a frontier, a vision, something to strive for. As a kid, McCaleb told friends that he would mine an asteroid someday. Now he wants to help people to live outside of the solar system. But he’s the first to acknowledge that Vast won’t work without a viable business model.

“It is a little hand-wavy, because this has never been done before,” says McCaleb, of creating a working business out of launching and running a commercial space station. “[Space is] an emerging market, and we’re not exactly sure how it’ll shape up. But I’m pretty sure if people want to be a part of it, then we will need habitation.”

Theoretical as it may be, space startups and industry analysts alike paint the race to replace the ISS as essential for the future of the commercial space industry. Vast and its ilk are seeking to create what’s essentially an office in the sky for NASA, which would attract the billions of dollars the agency has traditionally spent on the ISS every year and help develop (very valuable) human habitation tech for moon and Mars missions. “We’re not building a space station, we are building an economy,” says Brad Henderson, chief commercial officer of Starlab Space, one of Vast’s more established competitors. “This is a piece of commercial real estate that is continuing on the legacy of what the world has done [with ISS].”

But space station competitors also want to create a base for futuristic, low-gravity manufacturing, which has been shown to impact—and even optimize—crystalline and molecular growth. Haot calls microgravity manufacturing the “holy grail.” Startups have already shown that manufacturing in space can lead to more pure fiber-optic cables, called ZBLAN, and pharmaceuticals. Southern California startup Varda has manufactured more pure versions of the HIV drug ritonavir on its satellite.

“You know that 30-year period when we went from biplanes made of cloth in the 1920s to traditional commercial jets in the ‘50s—when aircraft went from the domain of reckless people to an experience for everyday business travelers?” says Peck, from Cornell. “That’s kind of where we are right now with space.”

The potential of getting the next-gen space station right has some worried about what might go wrong. Starlab’s Henderson frames the competition as a battle between companies with competence and experience and newer players that are trying to fast-track the engineering and launch process. His company is a collaboration between Mitsubishi, Airbus, Palantir, and Northrop Grumman. He sees the rightful successor to the ISS as coming from a company that can build international alliances, foster a space economy, and be a methodical, safe builder (Starlab doesn’t plan to launch anything until mid-2029). To him, going really fast isn’t the answer, and may be a liability.

“If you’re trying to verticalize a brand-new company in a brand-new way, get it 100% right the first time, and go like a bat out of hell, the likelihood something small will go wrong, and you could have catastrophic failures, is high,” he says.

Minimum viable station

Two things led Haot to becoming the CEO of Vast. The first was a tour of Cape Canaveral that he took in 1985 while visiting the U.S. as an 11-year-old. Cape Canaveral is where, if all things go right, the Falcon 9 rocket carrying Vast’s Haven-1 station will launch next year. The second was his partial success with a startup he founded and ran, called Launcher, which attempted to build a rocket quickly and cheaply. With just $30 million and an assist from SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket, the firm put a pair of satellites into space in 2023, though they failed shortly after deployment. The company also landed a government contract to develop its rocket technology, though it never launched. The scrappy operation impressed McCaleb when he met Haot in 2022. Haot was seeking funding. McCaleb countered by acquiring Launcher in February 2023 and putting Haot in charge of day-to-day operations at Vast.

McCaleb had stepped away from Ripple a few years earlier and, looking for the next chapter, began looking into starting a space company. He talked to friends, and friends of friends, speaking to anybody who knew about the industry, until he found himself in a hotel in Marina Del Rey in the summer of 2021 with a trio of engineers, including Colin Smith, who’s still with Vast. They started laying out a strategy to win the NASA contest for an ISS replacement.

First, they’d focus on the station module itself and not worry about creating a launch system; they’d utilize SpaceX and the Falcon 9 to get the capsule into space. Second, they’d look to create a minimum viable product. Initially, the team wanted to build a more elaborate module with artificial gravity (a concept still in Vast’s long-term game plan). But the initial launch, Haven-1, will be smaller, with the station set to orbit for just three years, but only have humans on board for separate, 10-day missions.

Haven-1 will be a leap forward from the cramped, utilitarian quarters of the ISS, with a sizable viewing port, Starlink internet access, interior wood paneling, and white walls that recall a spa. It won’t, however, include facilities like a bathroom, or be habitable beyond short stints in space.

During crewed missions, the SpaceX Dragon spacecraft will dock with Haven-1, and, to the relief of astronauts, provide access to a working bathroom and a means of leaving in case of an emergency.

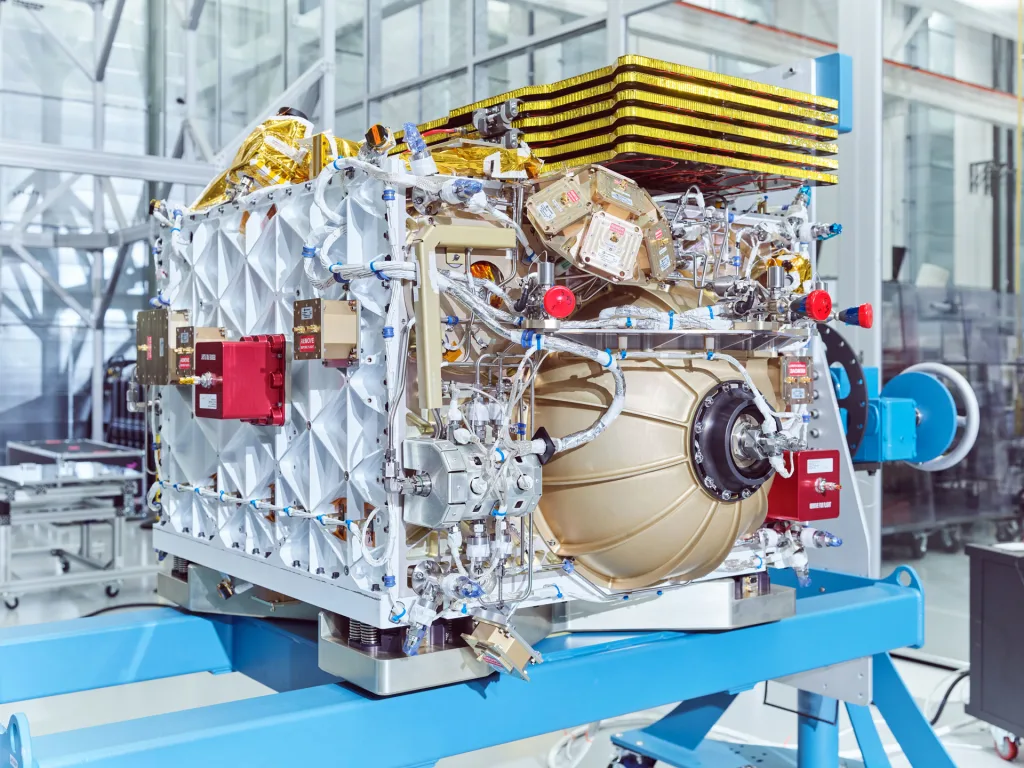

These choices allow Vast to build a smaller, lightweight structure—and to do most of it in-house. The Vast team is shaping and welding Haven-1’s aluminum form, along with designing and manufacturing its own batteries and avionics. It’s even sewing the crew’s uniforms, thanks to a team of seamstresses who sit on the factory floor. Being vertically integrated, argues Haot, means you don’t waste time and money outsourcing key components

Melden Sie sich an, um einen Kommentar hinzuzufügen

Andere Beiträge in dieser Gruppe

Before generative AI, if you wanted an inexpensive way to build out lo

Banks are embracing the AI workforce—but some institutions are taking un

For those who’ve had enough of scrolling AI slop, meet Picastro: an In

The Republican Party’s 800-page One Big Beautiful Bill Act is now being debated i

Colombian gangs are using social media to reach and recruit children, the United Nations has warned.

Gangs and rebel groups are enticing children to enlist by posting videos on platforms