A gleaming Belle from Beauty and the Beast glided along the exhibition floor at last year’s San Diego Comic-Con adorned in a yellow corseted gown with cascading satin folds. She could barely take two steps before a cluster of little girls stopped her for photos. As she waved one hand, her other delicately held a red flower with mechanized fingers. The kids stared. It’s not every day you see a fairy-tale princess with a cybernetic hand. Disney meets Skynet. But this being the epicenter of the nerd universe, the mash-up slayed. “Oh, cooool,” one of them cooed.

For Mandy Pursley, the 42-year-old graphic designer cosplaying Belle, it was a chance not only to show off her enviable sewing chops, but also to display the bleeding-edge technology that overhauled her life. Pursley was born with a right arm that ended just below her elbow. She began wearing prosthetics at age 6 but grew disillusioned with them a few years later. “I didn’t find it to be very functional or very useful,” she says.

Over time, her left hand overcompensated. She accomplished tasks like typing 60 words per minute, but more nuanced dexterity eluded her. That is, until three years ago, when Pursley began using the Ability Hand, a state-of-the-art bionic prosthetic from San Diego startup Psyonic. Marketed as the first and fastest touch-sensing myoelectric hand, the device translates arm muscle movements from the residual limb into electronic signals that control the hand, while a haptic motor vibrates to indicate how tightly items are being grasped.

The results were game-changing. Before, Pursley often held objects with her feet. Now she tackles mundane tasks like opening a water bottle or threading a needle much more conventionally. “I’m able to use jewelry pliers now when I’m doing my costume making,” she says. “Before I would put the pliers in my armpit. It would hurt, and I didn’t have a lot of control over the really fine motions, like opening and closing them.”

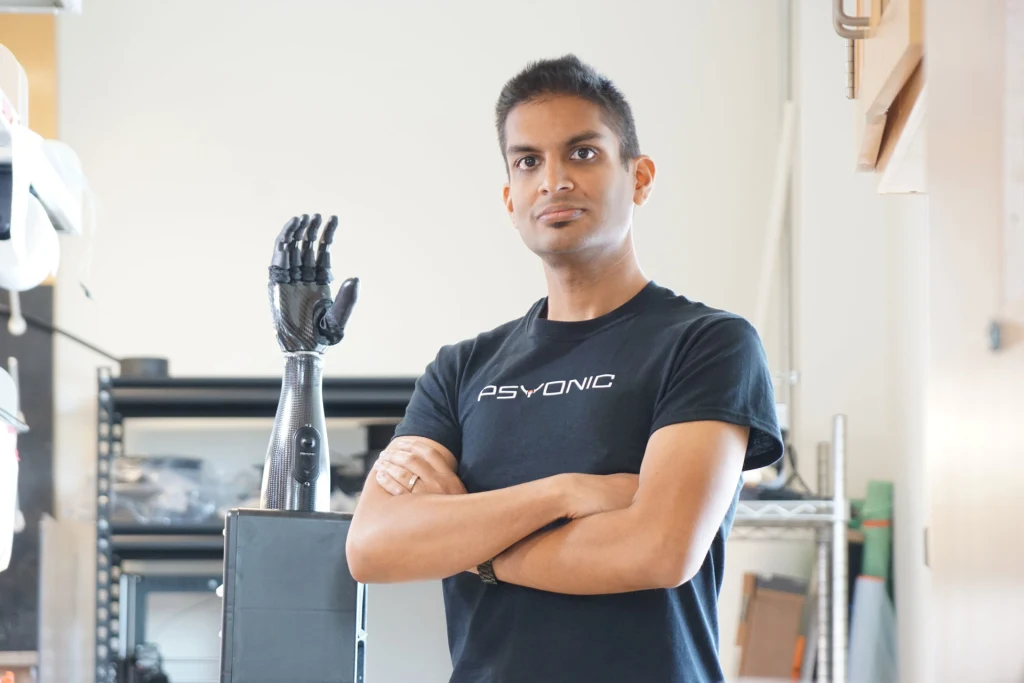

Pursley wasn’t the only bionic cosplayer at Comic-Con. She was part of a posse of Psyonic clients alongside Aadeel Akhtar, the firm’s 38-year-old founder and CEO and Ability Hand inventor, coursing through the convention after their panel, “Psyonic: Bionic Arms in the Real World,” which returns to this year’s event on July 24.

“It’s the world’s premier conference for sci-fi,” Akhtar says. “This is the current state of bionic technology, and what’s happening in science fiction is becoming a reality. We can demonstrate it at San Diego Comic-Con and show the world the cool stuff our users can do.”

Their presence is a natural here, given the pervasiveness of high-tech prosthetics in the sci-fi and comic universes. Marvel’s Bucky Barnes and Mad Max’s Furiosa sport bionic arms, while characters in the anime series Fullmetal Alchemist boast a range of mechanized limbs (not to mention the robotic hand Luke Skywalker receives in Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back after Darth Vader severs his real one).

But it wasn’t just sci-fi fans. The technology also caught the attention of science and film luminaries. Retired NASA astronaut Cady Coleman and Captain America: Brave New World production designer Ramsey Avery, at SDCC for panels, stopped to chat with Akhtar and examine the Ability Hand.

Avery recalls being awestruck by the machinery: “After years of cheating fake versions of functional artificial arms to look real for film or theme parks, there it was, the real thing!” Avery is returning to Comic-Con this year to conduct portfolio reviews on July 26. “It is so exciting to find myself living in the aspirational versions of the sci-fi I read as a kid, instead of the dystopian ones,” he says.

It’s the same “wow” factor that last year blew away the hard-won Shark Tank judges, three of whom—Lori Greiner, Daymond John, and Kevin O’Leary—agreed to " target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">invest a collective $1 million in exchange for a 6% equity stake, the particulars of which are still being negotiated. The device was also featured in a 2023 60 Minutes segment on University of Chicago prosthetic brain implant research.

Having amassed $4.1 million from equity crowdfunding and now valued at $65 million, the 10-year-old company has grown to more than 45 employees and broken even with a projected revenue of $6 million this year. It’s now in the process of relocating to a nearby 22,000-square-foot manufacturing facility, almost five times the size of its current digs, and considering an eventual IPO to scale up manufacturing.

Psyonic’s hands are used by nearly 250 patients and more than 50 of the world’s top robotics researchers, institutions, and companies, including NASA, Meta, Google, Mercedes-Benz, and MIT. Nonhuman applications range from automated assembly to service robots. Two years ago, the company introduced Abi the Ability Dog, a demonstration robotic dog that uses an Ability Hand to turn doorknobs and " target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">wield lightsabers. Meanwhile, NASA is readying an Ability Hand-sporting humanoid robot named Valkyrie for a future space mission.

“We’re making over 1,000 hands a year, at $15,000 to $20,000 apiece, for both a human and humanoid robot marketplace that will explode in the next five years,” Akhtar says. “But we need to scale this to where we’re making tens to a hundred thousand hands per year. Our biggest issue right now is that we’ve got more demand than we can produce.”

Much of that growth allows putting considerable energy back into innovating. Earlier this year, Psyonic released a lighter, faster, and more durable upgrade with a stronger grip and conductive fingers for cellphone use, with plans to roll out a fully redesigned Ability Hand by 2027. Meanwhile, it’s concurrently working on a next-generation interface enabling more nuanced individual finger control and a localized sense of touch. This approach involves implanting electrodes in the residual limb nerves and titanium rods in the bones. The electrodes carry signals between the nerves and the hand along wires inside the rods.

Akhtar also intends to adapt the technology for partial-hand amputees and to create an Ability Leg. “I see a more seamless interaction between humans and machines, where this feels like an extension of your body as opposed to just a tool on the end of it,” he says.

What makes the tech so special?

The Ability Hand is two and a half times faster than its competitors (closing as fast as 0.2 seconds) and the first with touch feedback, Akhtar says. It attaches to a custom-molded arm prosthetic, or “socket,” that’s made separately by prosthetic clinics, and grips the residual limb by extending over the bony protrusions flanking the elbow. The user’s brain sends signals to the limb muscles as though to move an actual hand, causing them to expand and contract. Two sensors in the socket detect those movements, amplify them, convert them into electrical signals, and transmit them to the Ability Hand, causing the grip to open or close. Users can connect to a smartphone app via Bluetooth to create customized grips and display data such as muscle signals and touch feedback. An internal haptic motor vibrates according to grip strength to let users know how firmly they’re grasping things and give them the sensation of pressure.

Batteries last six to eight hours, depending on use, and recharge in an hour by plugging the socket into a wall. There are also a couple of nifty perks: The hand plays a synthesized version of the Doom video game theme song and can also charge phones. (“I wish I could do that with my natural arm!” Akhtar says with a laugh.) Psyonic offers a selection of colors—blue, white, green, rose gold, and black—and attachments like a wrist rotator that can turn hands 360 degrees.

Both the Ability Hand and socket are typically made from carbon fiber—the same material used in rocket parts—rendering them lightweight but able to take a beating, with silicone and rubber in the fingers enabling flexibility.

“I can smash this, it totally survives,” says Akhtar, waving a model Ability Hand. “I’ve dropped it from the roof of my house, 30 feet in the air. I put it in the dryer for 10 minutes. I’ve stepped on it. We’ve done flaming board-breaking with it. I arm-wrestled a U.S. paratriathlon national champion and lost. It’s also one of the few that’s water resistant, so you can wash it like you would a natural hand, though you can’t submerge it yet.”

That toughness makes more activities possible. “I’m very hard on my prosthetic devices,” says Kate Ketelhohn, 22, who was dressed as Bo Peep from Toy Story. “I do theater, and it would break during a show. The director would want me to do certain tasks and I couldn’t do them because my hand couldn’t handle it.”

A graduate student in bioethics and medical humanities at Case Western Reserve University, Ketelhohn has been using the Psyonic device since her senior year of high school. As an infant, she lost her left forearm, right-hand fingertips, and feet from sepsis and meningitis, and has worn prostheses since she was a toddler. But the muscle-powered hook she used during childhood couldn’t quite cut it.

“The devastation as a kid when you just keep trying to eat chips and keep crumbling them because your hand can’t handle fine delicate movement,” she says. “Now, being able to eat chips or carry food in one hand and eat it with the other feels like a complete life hack. People with disabilities, especially with upper-limb differences, have such possibilities to work and function at a pretty normal able-bodied level if we have access to the right tools.”

A life-changing trip

Akhtar has wanted to build bionic limbs since age 7 after traveling with his parents to their native Pakistan and seeing a girl his age missing her right leg and using a tree branch as a crutch. “It just stuck with me,” he says. “We had the same ethnic heritage, but vastly different qualities of life. A lot of it has to do with having access to things like affordable rehabilitative care and advancements, like bionic limbs.”

He studied biology at Loyola University in Chicago, his hometown, intent on becoming a neurosurgeon, until a computer class captured his imagination. “I loved everything about coding and programming and making my own things. I realized that if I became a straight-up MD I wouldn’t get to do any of the cool stuff I was learning in my computer science classes.” Akhtar also drew inspiration from breakthrough research at the time that used nerve impulses to control prosthetics. “I wanted to figure out a way to merge my interests in prosthetics, clinical medicine, and engineering to help people with limb differences regain function and improve their quality of life.”

Akhtar went on to earn two master’s degrees in computer science and electrical and computer engineering at Loyola and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, respectively. He was on an MD/PhD track at the latter when he got the chance to work with the Range of Motion Project, an Ecuadorian nonprofit that provides prosthetics to those who can’t afford them. Its first patient was Juan Suquillo, an Ecuadorian Army veteran who’d lost his left hand during a 1981 border war with Peru. Akhtar watched Suquillo tear up after donning an early version—three times his hand size, with wires everywhere—and pinching his left fingers together.

Login to add comment

Other posts in this group

Twitter cofounder Jack Dorsey is back with a new app that tracks sun exposure and vitamin D levels.

Sun Day uses location-based data to show the current UV index, the day’s high, and add

AI chatbot therapists have made plenty of headlines in recent months—s

The latest version of Elon Musk’s artificial intelligence chatbot Grok is echoing the views of its

When an emergency happens in Collier County, Florida, the

The internet wasn’t born whole—it came together from parts. Most know of ARPANET, the internet’s most famous precursor, but it was always limited strictly to government use. It was NSFNET that bro