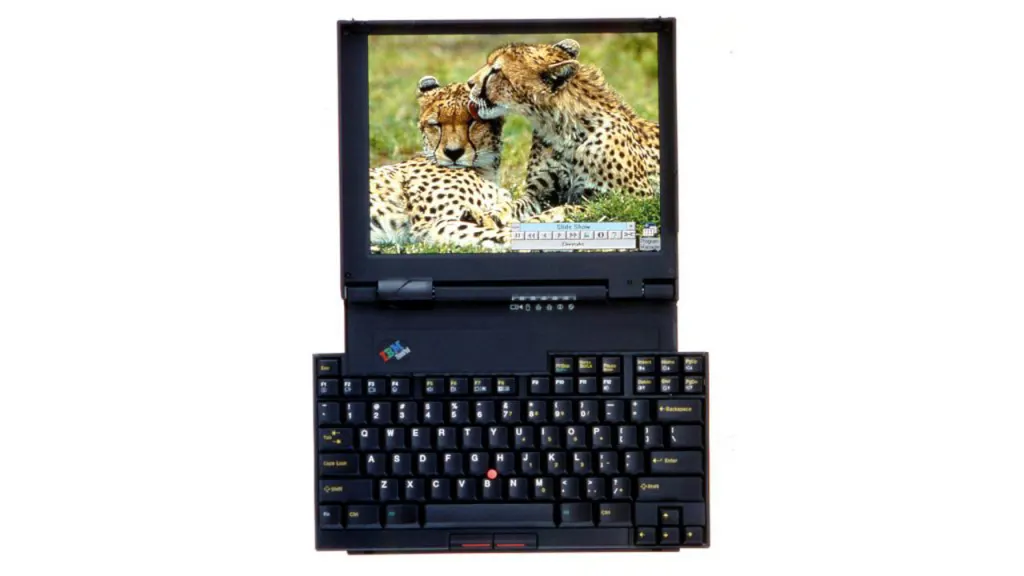

Closed, it looks pretty much like any other laptop manufactured in 1995.

To be sure, it’s more compact than most—making it, in the parlance of the day, a subnotebook. But it’s still comically thick, standing almost as tall as four MacBook Airs stacked on each other. That height is required to accommodate multiple technologies later rendered obsolete by technological progress, such as a dial-up fax/modem, an infrared port, two PCMCIA expansion card slots, and a bulky connector for an external docking station.

But then you open it up. And as you do, something utterly unique happens.

Thirty-five of the laptop’s keys glide out to the left in a cluster. Another 49 swivel downward and to the right. By the time you’ve raised the screen into place, those 84 keys have assembled themselves into a keyboard that’s 11.5” wide—even though the laptop’s case is only 9.7” wide. The result is the holiest of 1990s computing holy grails: comfy, no-compromises typing on a laptop that is—again, by the standards of three decades ago—highly portable.

This story is part of 1995 Week, where we’ll revisit some of the most interesting, unexpected, and confounding developments in tech 30 years ago.

I could only be talking about IBM’s ThinkPad 701, the most buzzworthy PC of 1995. Its expanding keyboard, officially called the TrackWrite, remains better known by its code-name of “Butterfly,” referencing the spreading-wing-like effect as it slid into place. (IBM’s butterfly keyboard is not to be confused with Apple’s much later, famously wretched keyboard of the same nickname.)

Most amazing tech products don’t stay amazing forever. “Amazing—for its time” is generally as good as it gets. But I don’t hesitate to describe the ThinkPad 701 as amazing, full stop. It’s one of the best things the technology industry has ever done with moving parts.

Though the concept may sound faintly Rube Goldbergian, it worked shockingly well. Lifting the screen set off a system of concealed gears and levers that propelled the two sections of keyboard into position with balletic grace. Once assembled, there was no visible seam between the sections, and—despite the overhang they created on both sides of the computer—no droop. Closing the lid neatly reversed the process.

Even the confident sound the keyboard produced as it slid in and out—somewhere between a whirrrr and a whooosh, culminating in a satisfying click—was pleasing to the ear, as if IBM had paid attention to the acoustic experience in its own right.

Most computers would be hard to sell in a 15-second TV commercial. But all IBM had to do was convey the ThinkPad 701’s petite size and then show what happened when you opened it. Mission accomplished, with time to spare.

Long after the ThinkPad 701 left the market, it still felt like magic. David Hill, who became the ThinkPad’s design chief in 1995 and continued in the role after IBM sold its PC division to Lenovo a decade later, kept one on hand to demonstrate to visitors such as college students. “Every time I pulled that thing out and showed it to people, the reaction would be the same,” he remembers. “There would be this deafening silence. And then someone would say, ‘Do it again!’”

When the ThinkPad 701 was new, laptop buyers recognized it as the engineering marvel it was. A Businesweek article cited sales of 215,000 units and said it was 1995’s best-selling PC laptop. Yet by the time that story appeared in February 1996, the 701 had been discontinued. IBM never made anything like it again. Neither did anyone else.

So how could a laptop widely regarded to have solved one of mobile computing’s fundamental problems come and go so quickly? Therein lies a tale.

The subnotebook conundrum

If you skim through enough photos of typical laptops of the mid-1990s—such as the 65-plus models reviewed in an August 1993 PC Magazine cover story—two things will strike you about their displays. First, they’re truly dinky. Nearly all the ones PC Mag covered measured between 8.5” and 9.5” diagonally. Today, by contrast, most mainstream laptop screens start at 13” and go up from there.

Secondly, most mid-1990s laptop screens are surrounded by overwhelmingly gigantic bezels, as if they were framed, matted photos. From our 21st-century vantage point, they look weird, since computer makers later spent years shrinking the bezels down—both an aesthetic improvement and a way to fit a roomier display in a smaller case. But by supersizing the bezels, ’90s manufacturers gave themselves enough room to equip laptops with desktop-like keyboards. At the time, even more than now, that was an absolutely critical design goal.

The first PC maker that figured out how to design a subnotebook-sized laptop with a desktop-sized keyboard would really have something.

Now, there were buyers who craved portability so much that they were willing to accept a shrunken keyboard. Subnotebooks catered to them. But these miniature laptops were a quirky niche. Reviewing the ThinkPad 500, IBM’s first subnotebook, for InfoWorld in 1993, my friend Fredric Paul concluded that “touch typing is possible but not exactly fun. A bit more thought about the proper form factor might have allowed more pleasant typing.”

Everyone else making subnotebooks faced the same issue. ”There was a mismatch between the largest-size screen and a full size keyboard,” says Hill. “If you wanted to make something that essentially hugged to the sides of the screen, the keyboard had to be significantly compromised in terms of the ability to type on it.”

It was obvious that the first PC maker that figured out how to design a subnotebook-sized laptop with a desktop-sized keyboard would really have something. Unless, that is, the whole thing was an impossible dream.

In 1992, design legend Richard Sapper had given the first ThinkPad its squared-off black case and red TrackPoint pointing nub—elements that have proven so durable that they’re still with us in new ThinkPads from Lenovo. As IBM contemplated the subnotebook market, Sapper tinkered with methods for getting big keyboards into small laptops—“Folding the keyboard on top of itself, with wings that would fold outward, and some other ideas,” says Hill. “But they made the computer thicker. And that was not something that was popular.”

Impractical though the goal of a keyboard that expanded seemed, it continued to float around within IBM. Among those trying to solve it was John Karidis (1958-2012), an employee at the company’s Yorktown Heights, New York, lab whom Hill calls “the most gifted mechanical engineer I’ve ever worked with in my entire career.” His previous projects at IBM had ranged widely, from high-speed printers to chip testing equipment.

Karidis “really enjoyed the cadre of inventors and makers,” say his brother, George Karidis—an inventor himself, as was their father, a nuclear engineer for Westinghouse. “He welcomed that [IBM] was International Business Machines, and he and others made machines. He had a deep concentration at a moment’s notice on any topic. He didn’t have a fear of failure, but just an eagerness to pursue things.”

One day, Karidis had the epiphany that made the ThinkPad 701 possible. “He was playing with some wooden building blocks with his daughter, and he noticed that if you take two triangular blocks and slide them past each other, it kind of makes a rectangle that changes its aspect ratio,” says Hill. By breaking a keyboard into sections that slid, you might be able to increase its width without resorting to a folding design that added to the computer’s height.

To test that idea out, Karidis “ended up photocopying a keyboard and then cutting it out,” says his brother George. “He saw how it could translate. And he went home and showed it to his wife, and she kind of looked at him funny and said, ‘’They pay you to do this?’”

IBM used robots to verify that the split keyboard was robust enough to withstand 25,000 openings and closings.

In his 2017 book How the ThinkPad Changed the World and is Shaping the Future, Arimasa Naitoh, who led a ThinkPad engineering team in Yamato, Japan, for decades, writes of an IBM executive at the company’s Raleigh, North Carolina office. Learning of Karidis’s keyboard, he pushed a plan to incorporate it in a laptop. That executive, Naitoh says, was Tim Cook—years before he joined Apple. Cook’s IBM responsibilities involved manufacturing and distribution, not product development, and he left the company well before the ThinkPad 701 was released. Thinking of him as one of its fathers may be going way beyond the documented evidence. Still, the mind boggles: The most interesting laptop Apple’s eventual CEO played a hand in hatching might not have been a MacBook.

Bringing Karidis’s brainstorm to market took time. In 1992, the company had formed an analysts’ council that gave a select group of industry watchers the opportunity to see products under development and provide feedback. Its participants included Creative Strategies analyst (and Fast Company contributor) Tim Bajarin; the group still exists today as part of Lenovo’s PC business and Bajarin remains a member.

At one meeting, the council got a preview of Karidis’s design—though not yet in a working laptop. ”It wasn’t a true device, but they showed us the concept, showed us how the butterfly keyboard might work,” explains Bajarin. “And by the way, they did really good mockups. They were not cheapo stuff. To a person, we said, ‘If you can do it, you should do it.’”

They could do it, and did—just not as rapidly as they’d hoped. Naitoh writes that the ThinkPad 701 was initially supposed to ship by the end of 1994. It missed that deadline, delayed by the demands of engineering and testing such an unprecedented product. For example, IBM used robots to verify that the split keyboard was robust enough to withstand 25,000 openings and closings.

Mr. Bond’s laptop

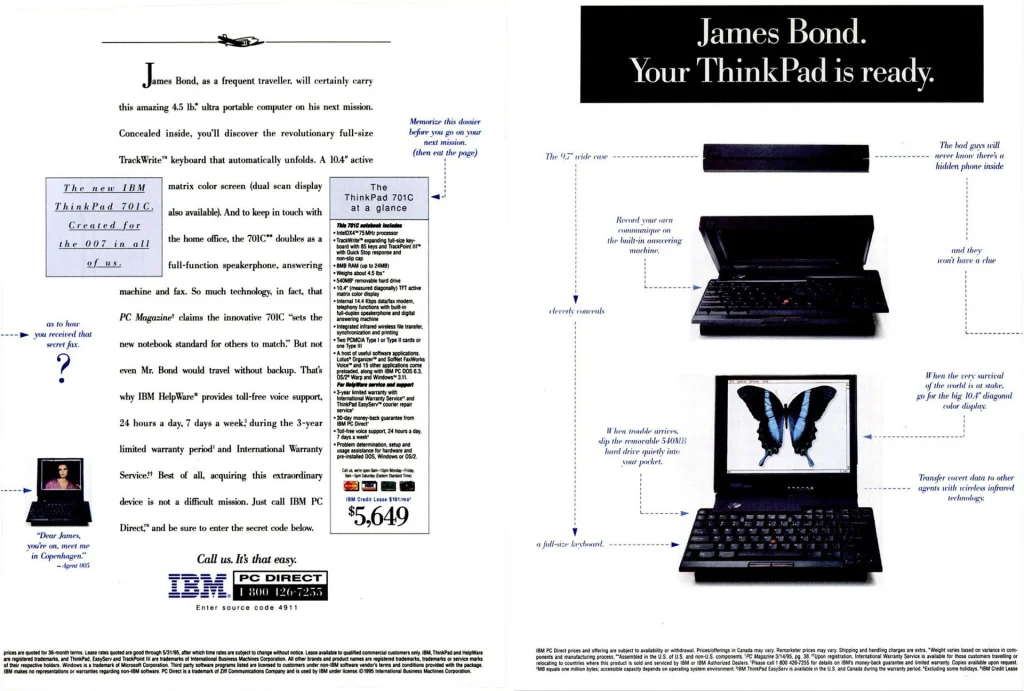

On March 6, 1995, IBM finally announced its new subnotebook. Available in a variety of configurations, its list prices ranged from $3,799–$5,649, or about $8,000–$11,900 in 2025 dollars—not cheap, but not absurd at the time. The most economical variant, the ThinkPad 701Cs, had a 10.4” screen—roomy at the time—but it was a “passive matrix” LCD, which tended to leave colors looking a tad washed out. The one you really wanted was the 701C, which sported a vivid active-matrix screen of the same size.

In a story about the 701’s arrival, The New York Times’ Laurie Flynn said that IBM might have trouble keeping up with demand, in part because it had gotten prospective buyers too excited too early. She also noted that the 701 used “the older Intel 486 chip rather than the faster Pentium”—an artifact of its slow gestation that would come back to bite IBM.

Reviewers, whom IBM had seeded with ThinkPad 701 units before its release, weren’t impressed by the laptop’s aging processor and found its battery life iffy. Thanks to the butterfly keyboard, they still hailed the system as a mobile computing landmark. “The $5,000 ThinkPad 701C has successfully taken the sub out of subnotebook,” wrote PC Magazine’s Brian Nadel. The Wall Street Journal’s Walt Mossberg called it “a true gem of a computer” and—more than 20 years later—“probably the most unusual and, I think, in some ways clever laptop I ever reviewed.”

Generally speaking, IBM was a businesslike brand and ThinkPad marketing leaned into practical advantages. With the 701, however, the company wasn’t afraid of gadget-y associations. ”James Bond, as a frequent traveler, will certainly carry this amazing 4.5 lb. ultra portable computer on his next mission,” declared one ad, playing up features such as the built-in answering machine and fax capability. That November, James Bond (Pierce Brosnan) really did fool around with a 701 in GoldenEye—although only fleetingly and to the apparent annoyance of Q. (Fittingly, Hill says that Karidis was known as “the Q of IBM.”) The following year, the computer also showed up briefly in Tom Cruise’s first Mission Impossible film, which is better known for its Apple product placement.

In this video promo shot at Disney World’s Epcot Center,an IBM employee walks through the 701’s features. We also glimpse the equipment the company used to test the computer and random theme park visitors being impressed by the expanding keyboard.

The ThinkPad 701 garnered some weighty recognition, including 27 design awards. It was even exhibited at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art. But despite the publicity and plaudits, its clock ran out before the year ended. In a “Hardware Withdrawal” list released on November 21, 1995, IBM announced that it would stop marketing the 701 as of December 21. Units that had already made their way into distribution channels would remain available into 1996, but the 701 was a dead computer walking, less than nine months after its debut.

Multiple factors contributed to IB

Accedi per aggiungere un commento

Altri post in questo gruppo

The latest version of Elon Musk’s artificial intelligence chatbot Grok is echoing the views of its

When an emergency happens in Collier County, Florida, the

A gleaming Belle from Beauty and the Beast glided along the exhibition floor at last year’s San Diego Comic-Con adorned in a yellow corseted gown with cascading satin folds. She could bare

The internet wasn’t born whole—it came together from parts. Most know of ARPANET, the internet’s most famous precursor, but it was always limited strictly to government use. It was NSFNET that bro

Closed, it looks pretty much like any other laptop manufactured in 1995.

To be sure, it’s more compact than most—making it, in the parlance of the day, a subnotebook. But it’s still comi

IShowSpeed and Jynxzi are teaming up to host a $100,000 Fortnite tournament, bringing together 100 top creators for what’s shaping up to be the biggest celebrity Fortnite match to date.