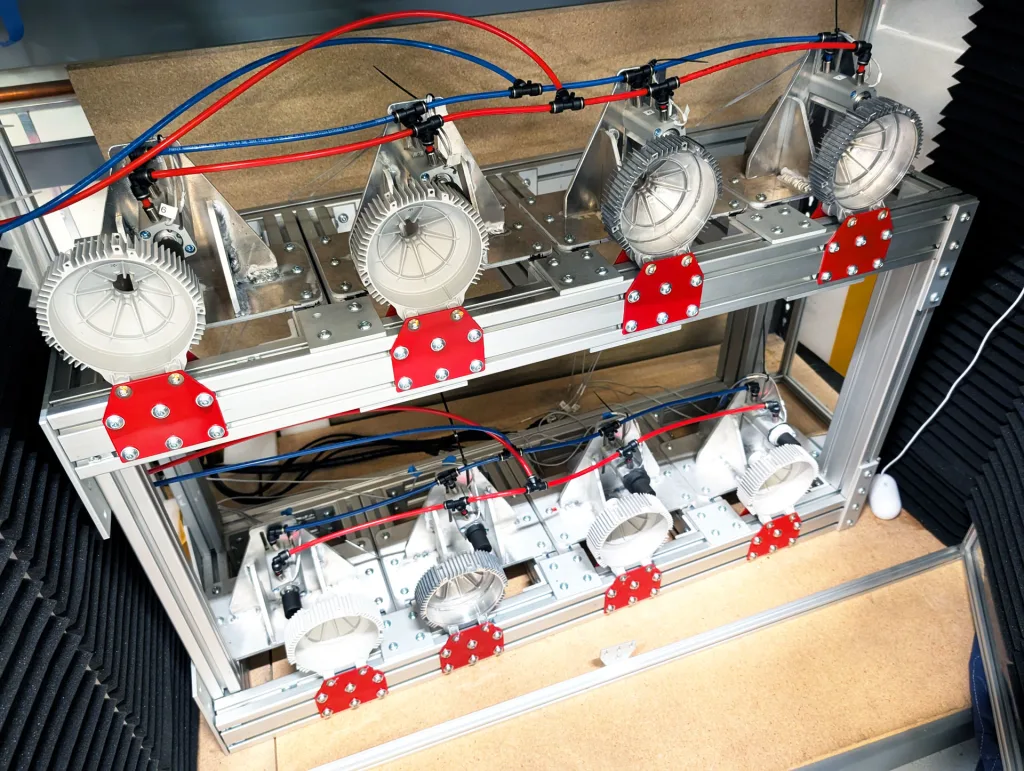

If you think drones are noisy in flight, try building and testing them. During a visit last month to the drone startup Zipline’s factory in South San Francisco, California, industrial noise welled up in corners of the facility—the roar of a wind tunnel, the rhythmic clack of a test rig simulating motor casing wear, and other mechanical sounds in a symphony of engineering.

Zipline has to subject its delivery drones to that kind of abuse because it’s been building them in-house since 2016—a strategy management sees as wiser than relying on outsourced manufacturing. “Zipline has intentionally designed ourselves as a very vertically integrated company,” says Eric Watson, head of systems engineering.

The company’s facility, located just below the flight path of jets departing San Francisco International Airport, combines warehouse, assembly, and testing space.

That, Watson says, lets the company iterate rapidly and frequently. “We can quickly get the design engineer who built the thing to look at it,” he tells Fast Company. “And then we can update the test, update the drawing, whatever needs to happen.”

Founded in 2014, Zipline (one of Fast Company’s picks for 2024’s Most Innovative Companies) began delivering medical supplies in Rwanda in 2016. Today, it bills itself as the largest commercial drone delivery service. The live display on its site counts more than 1.5 million deliveries to date; over a two-hour period on Saturday, that counter showed another 48 had been completed. (For comparison, Wing, the drone-delivery service owned by Google’s parent company Alphabet, says it’s made more than 450,000 residential deliveries.)

In the U.S., Zipline offers Walmart customers the option of drone deliveries in the Dallas-Fort Worth area and Pea Ridge, Arkansas. (404 Media found that Zipline had recently supplied the Pea Ridge mayor with talking points that then ran almost verbatim in a blog post on the company’s own site)

Zipline makes two battery-electric drone designs. It describes its older Platform 1 aircraft (or P1) as optimized for deliveries of up to 4 pounds to “enterprise, business, and government” customers over distances up to about 60 miles from a Zipline-operated delivery hub. The newer Platform 2 (P2) is built for home delivery from third-party sites, able to carry twice as much payload but with a service radius of only 10 miles. And where P1 drops its payload via parachute, P2 spools it down under a 300-foot winch in a cargo compartment that has its own fans to guide its descent to a precise spot on the ground.

Watson described the adoption of that winch architecture as a lesson learned about the difficulty of trying to keep a drone hovering directly over a delivery point in the wind: “We now move the aircraft upwind.” That setup also keeps the whir of a Platform 2’s five combined rotors 300 feet away from people on the ground, where the company says that noise is “nearly inaudible.”

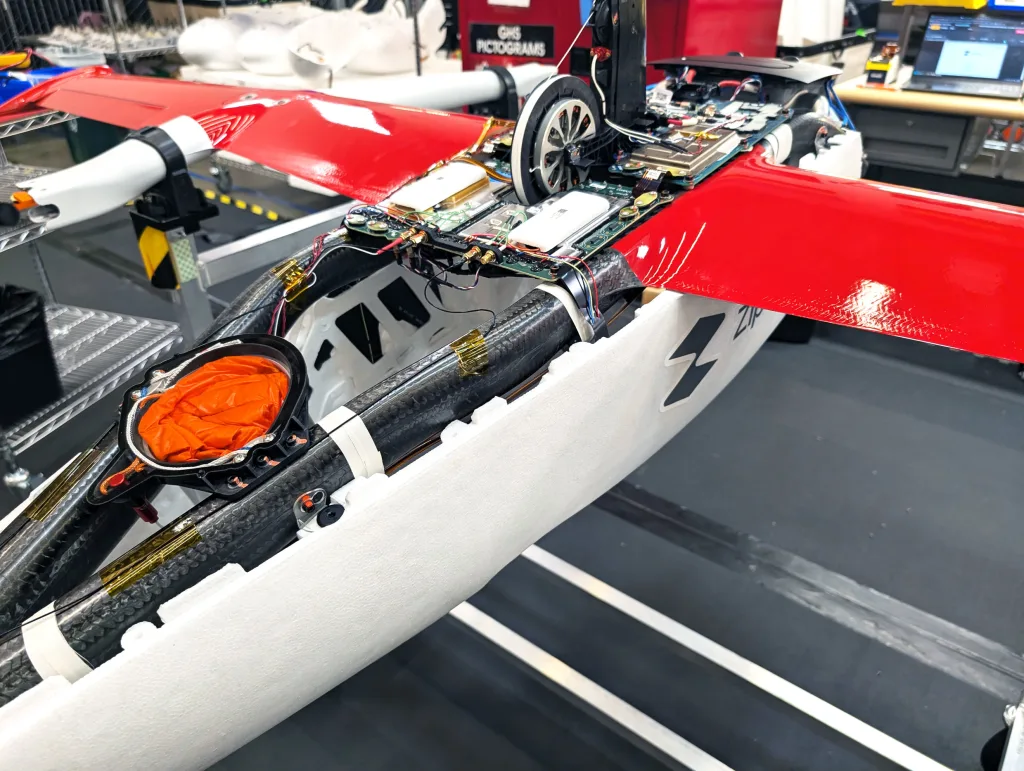

P2 drones depart from and return to the underside of a landing dock, nestling a connector at the top of their fuselage into the well of that contraption. During my visit, the factory’s operations looked focused on P2. Racks of that aircraft’s laughably light carbon fiber assemblies of wings and rotor nacelles sat in one corner of the building (I easily picked one up), test stations for components scattered around, and at a series of assembly stands in the middle, workers performed such tasks as attaching a P2 drone’s two redundant system boards.

Amid signs warning of the dangers of testing hardware with spinning propeller blades—one outside a closed door warned of a “high-risk test area with extremely loud noise levels and moving equipment”—there were moments of whimsy and warmth.

The first Platform 2 models required two to three days of work, but the company can now crank out three a day. “We have made a ton of progress with our Platform 2 manufacturing,” Watson says. “Later this year we should be producing an aircraft every hour.”

Zipline, however, doesn’t fabricate every single component itself. Beyond standardized parts such as fasteners, it has its own network of suppliers building subsystems—for instance, the carbon fiber airframes—to its specifications. “The way that we have trended over time is bringing more things in house,” Watson says.

Labels on some incoming boxes noting their origins in China or Vietnam provided a reminder that this company remains exposed to President Donald Trump’s tariffs—if much less than drone services relying on consumer drones built in China.

“We do have a global supply chain,” Watson says, adding that Zipline’s vertical integration “does allow us quite a bit of flexibility” in suppliers.

The entire field of drone delivery has exhibited some of the same problems of too-soon hype as other tech frontiers. Amazon’s highly publicized venture into drone delivery has made legitimate advances but remains vaporware for almost all of the retail giant’s customers.

The business model also remains unclear. Privately-held Zipline doesn’t disclose revenue, per-delivery costs, or headcount, although funding that Crunchbase puts at $821 million does give it a long runway to work with.

Zipline also has the advantage of having secured Federal Aviation Administration authorization in September of 2023 to operate drones beyond an operator’s visual line of sight (BVLOS), with automatic broadcasting of their location to other aircraft and altitude limits in place.

In a January 2023 report, the consulting firm McKinsey emphasized the importance of BVLOS operation in letting drone-delivery services cut per-trip costs from what it estimated at $13.50 with one operator assigned to a drone to $1.50 to $2 with one operator supervising 20 at a time.

In October, a subsequent McKinsey post highlighted a vast potential market—“$5 billion by 2035, with approximately 1.5 billion annual deliveries expected”—but warned that a customer survey it ordered up had revealed relatively low interest in drone delivery among U.S. customers.

That survey found that 53% of U.S. respondents said they were willing to switch to drone delivery, but only 37% were willing to pay a premium. Both shares were the lowest observed in the six countries surveyed: Brazil, China, Germany, India, Saudi Arabia, and the U.S.

That suggests that while the hardware and software of drone-delivery operations will need further iteration, the sales pitch itself remains in flight and may not land for a while.

Войдите, чтобы добавить комментарий

Другие сообщения в этой группе

Last week, Punchbowl News published an internal memo the National Republican Senatorial Committee (NRSC) sen

The internet’s favorite programming is back on: #RushTok season is officially upon us.

If this is your first time tuning in, “rush” is the informal name for the recruitment process

WhatsApp has taken down 6.8 million accounts that were “linked to criminal scam centers” target

For more than a decade, enterprise teams bought into the promise of business intelligence platforms delivering “decision-making at the speed of thought.” But most discovered the opposite: slow-mov

President Donald Trump on Wednesday is expected to celebrate at the White House a commitment by